The data is in! We’re eating more blueberries today than ever. In fact, there’s a 50% increase in consumption per capita in the last ten years. This is a global trend. Demand is high and there’s still plenty of reason for enthusiasm. Besides a growing fresh market, blueberries are finding their way into juices, jellies, and other processed products. Here are the facts!

Blueberries are now the second most popular berry in USA!

Blueberries in the USA are now at 2.3 lbs. per year per cap consumption (2022)!

Blueberries and eyesight – prevents macular degeneration!

Blueberries and memory – may slow onset of Alzheimers!

Blueberries are good for cardiovascular!

Blueberries fight aging – # 1 source of antioxidants!

Blueberries fight Cancer!

Blueberries are high fiber, high vitamin C, no fat, no cholesterol!

Janet Creech, professional vegan, is a blueberry eating expert

ABSTRACT

Rabbiteye blueberries, Vaccinium ashei Reade, were introduced as variety trials at Buna and Magnolia Springs, Texas in 1967 by Dr. Hollis Bowen of Texas A and M University. Performance data by the mid-1970s led to commercial plantings and by the mid-1980s a grower/marketing organization was established. Many of the early commercial plantings suffered from chlorosis and poor growth. Soil, leaf tissue and water quality standards established by Stephen F. Austin State University (SFA) provide the benchmark levels associated with good plant growth and production. The Texas Blueberry Marketing Association fractured in the 1990s and reorganized in southeast Texas with twenty-two growers. Several grower/packer/shipper groups exist today, as well as a viable pick-your-own, roadside and local sales industry. Current constraints center on frost at bloom, various insect and disease issues, and market difficulties. SFA continues to evaluate new germplasm as part of the USDA’s Southern Region Blueberry Germplasm Evaluation Program, and several advanced selections are under consideration for release.

HISTORY

The first planting of less than one hundred plants was established on the farm of Mr. Herbert K. Durand at Buna, Texas in 1966. A second planting soon followed at Magnolia Springs, Texas. Dr. Hollis Bowen, Texas A & M University (TAMU) pomologist, initiated rabbiteye blueberry varietal trials in East Texas based simply on the belief that rabbiteye blueberries, Vaccinium ashei Reade, a species indigenous to Florida and parts of Alabama and Georgia, could be grown in the acid soils of the Pineywoods of East Texas. East Texas normally receives 48 inches precipitation per year and lies in USDA Hardiness Zone 8. Most sites enjoy nearby sources of irrigation water and ready access to a number of organic soil amendments (pine bark, chips, straw, hay, etc.). In 1973, a larger trial under the direction of Dr. John Lipe was established at the Overton Research and Extension Center. The first plantings at TAMU, Overton, Texas, were primarily variety trials that included ‘Tifblue’, ‘Briteblue’, ‘Delite’, ‘Woodard’, ‘Garden Blue’, ‘Southland’, ‘Menditoo’, and ‘Bluegem’. In 2010, only ‘Tifblue’ remains a major part of the commercial picture. In addition, the first seedlings and selections of the USDA blueberry breeding program were cultivated at Overton, Texas. Paul Lyrene of the University of Florida led the charge in breeding southern highbushes, best characterized as the first early ripening varieties suitable for the fresh market.

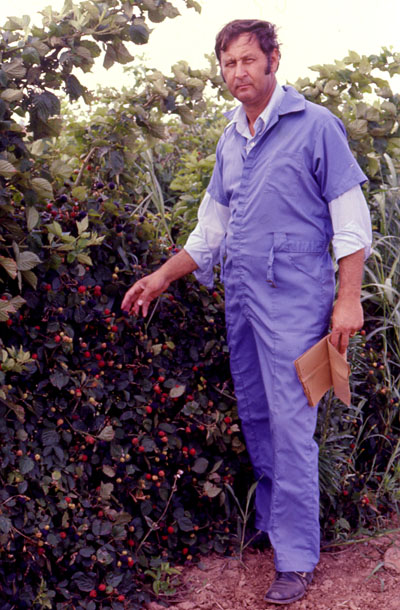

Dr. John Lipe, TAMU, Overton, TX in the late 1970s

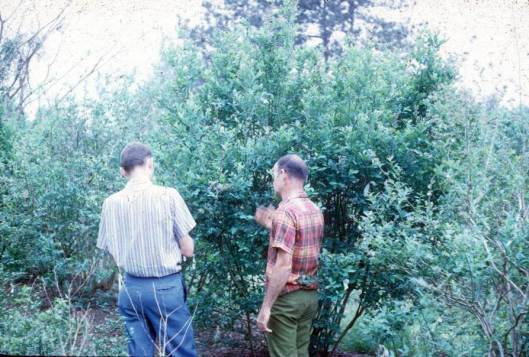

1970s? Rare picture of John Lipe and Herb Durand, Buna, Texas, first planting in Texas

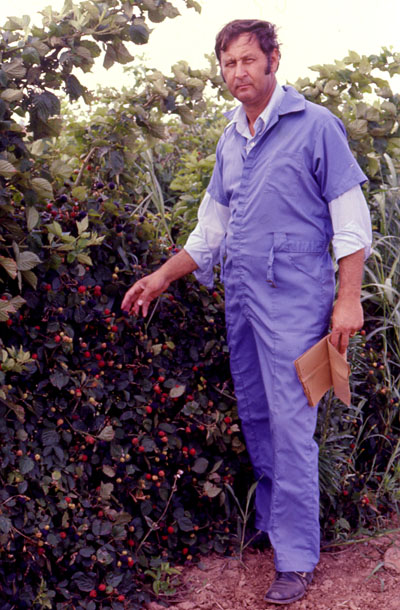

Dr. Hollis Bowen, TAMU, College Station, Texas in the late 1970s

Paul Lyrene, Univ of Florida, blueberry breeder

In the mid-1970s, the Texas Agricultural Extension Service began to report the results of variety and cultural trials at grower field days, conferences and events. Interest was high. Economic projections were optimistic. With yields of 12,000 lbs./acre predicted and market prices hovering around a dollar per pound, there was plenty of reason for grower enthusiasm. One of the very first fields in Texas was the field of Tom and Debbie Wild near Nacogdochs, Texas. This field was fraught with growth problems, later determined to be caused by marginal water quality from the deep well used on the property.

Very rare image of one of the first fields (mid 1970s), Tom and Debbie Wild, Nacogdoches, TX

The first large planting was that of Fincastle Blueberry Nursery and Farms, LaRue, Texas. Owner John Schoelkopf, Dallas businessman and horticulture enthusiast, dreamed of establishing a kind of horticultural “Disneyland.” While the farm initially embraced the direct-from-farm-to-consumer philosophy, the operation quickly grew into blueberry production levels beyond that marketplace. A great capital investment was made, consultants were hired, additional blueberries planted, irrigation systems were established via lakes on the property, and Fincastle began commercial production of blueberries and blueberry plants. The Texas Blueberry Growers Association was created in 1980. John Schoelkopf enthusiastically promoted the industry by hosting and partially subsidizing some of the first blueberry conferences in East Texas. As a result of field trial production data, good promotion and news releases, East Texas blueberry acreage increased.

Blueberry research in East Texas can be attributed to two academic units: 1) TAMU Research and Extension Center, Overton, Texas, and 2) the SFA blueberry research program. Due to budget cuts and the loss of the fruit scientist position at TAMU Overton, blueberry research ended there in the 1990s. At SFA, a modest program has continued with water quality experiments, germplasm trials, fertigation studies and field mulching/in-ground amendment work. In 2010, Texas blueberry acreage is estimated at 1100 acres. The Texas Blueberry Marketing Association operates primarily in southeast Texas with approximately 22 growers, 150 acres, and a focus on the southern highbush early production. Late spring frosts remain the most important constraint to high yields and growers have responded with sprinkler irrigation and large wind-generating fans.

RESEARCH ACTIVITES AT STEPHEN F. AUSTIN STATE UNIVERSITY

Blueberry research at this institution has been a long journey. Rabbiteye blueberries were first introduced fifty years ago. SFA’s blueberry research and extension program began in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The industry was young. Growers faced numerous challenges and growing guidelines were few. At that time, SFA’s research plots were a small fenced enclosure with irrigation at the SFA Dairy. In one of the first studies at SFA, we examined the growth of container-grown, large bareroot, and small bareroot rabbiteye blueberry nursery plants in the field (Creech and Dale 1982, Creech and Dale 1983). In that study, large bareroot and container plants were superior to small bare root plants at the end of the first and second years. Because of chlorosis and leaf symptom issues in our plots, we initiated a study to test the effects of four micronutrient rates, which failed to prevent chlorosis (White and Creech 1981). Thinking we might have an organic matter issue, we tested the influence of slow-release fertilizers and organic matter additions (pine bark and peat moss) on establishment of rabbiteye blueberries in the field (Bennett and Creech 1982). While growth was acceptable with the high organic matter treatments, chlorosis and growth appeared suboptimal. In a study of the influence of N source and rate on growth of Vaccinium ashei ‘Delite’ we found very few differences and less than acceptable growth (Creech and Young 1983a). We soon concluded that the problem lay with irrigation water quality. At that time, SFA research plots used City of Nacogdoches water as the water source. After studying blueberry farmer soil and water sample data in the SFA Soils Lab, Dr. Leon Young and I concluded that water quality might be a problem for many growers in the region. I had already noticed that farms using surface water were generally more vigorous than farms using well water. Dr. Young and I observed that pH values in the drip irrigation zone, while often optimal at the beginning of the season, soon increased in the drip irrigated zone to levels not recommended for blueberries. In another research project, while organic matter and slow release fertilizer treatments improved plant performance over controls, they did not compensate for the impact of poor irrigation water quality over the entire experimental block (Creech and White 1982, Young and Creech 1983). To test our suspicions, Dr. Young, Director SFA Soils Soil and Plant Tissue Testing Laboratory, and I initiated a study of the influence of sulfur sources and rates on soil pH and rabbiteye blueberry growth in the presence of high pH irrigation water (Creech and Young 1983b). The results indicated that sulfur and gypsum applications, while able to adjust soil pH values favorably, did not result in healthier plants. We concluded that high soil conductivities and continued high absorption of the Na ion was perhaps responsible for poor plant growth (Creech 1986d). We tested the impact of using Nacogdoches city water (350 µS/cm) and rain water on mist propagation of azaleas and rabbiteye blueberries and found that both rooted at higher percentages with rain water (Creech et al. 1985). With salinity issues affecting many new growers relying on deep wells, Dr. Kim Patten, TAMU, Overton, Texas, and I initiated a study that studied the influence of sodium on growth and leaf elemental content of ‘Tifblue’ rabbiteye blueberries (Creech et al. 1986). The project demonstrated dramatic leaf tissue Na level increases with only modest levels of Na in irrigation water. We concluded that growers using water with >50-60 PPM Na were facing problems, as Na appeared to accumulate over a few years to destructive levels.

Before application of fertilizers through drip systems became common place, growers in East Texas used a wide variety of means to deliver granular, generally acid-forming fertilizers. Some growers spread fertilizer by hand, particularly in the early years of a planting. Broadcast and banding applications were another common approach. We initiated a study on fertilizer placement both in the field and in “split-root” container studies (Creech 1986a). Split-root studies involve slicing the root system into halves or quadrants with a sharp knife, and then planting each root section into its own container, or planting in the field with a plastic barrier between sections. A small amount of raw uncut sphagnum moss around the wounded trunk results in a quick healing process. The result is a plant with four separated root systems, all feeding the same plant. Fertilizing on one side of the plant resulted in that side of the plant growing while the other side failed to produce significant new growth. We concluded that rabbiteye blueberries translocate nutrients differently than other plants. Results led to a number of interesting field studies. To see if the results of our split-root container study were transportable to field work, we split the root system of plants in the field by placing a plastic barrier between the right and left quadrants and soon learned that fertilizer placed on one side of the plant tends to affect that side of the plant. We concluded that growth and leaf tissue nutrient content was affected by fertilizer placement. Water transport studies involving four root quadrants indicated that as long as water was applied to half the root system, the plant was unaffected and growth was equal to plants receiving water in all four quadrants. However, water applied to one quadrant in container studies resulted in only slightly less growth, with shoot growth favored on that side of the plant receiving water. This led to SFA fertilizer recommendations, the importance of mulch, and an emphasis on the importance of applying a uniform distribution of fertilizer in a circle around the plant, or lightly banding down both sides of the row well away from the crown of the plant (Creech 1986b, Creech 1986c, Creech 1987a, Creech 1987c, Creech 1987d).

The shallow nature of rabbiteye blueberry systems triggered another study on the effect of shallow and deep placement of organic matter in the planting hole on root and shoot growth of rabbiteye blueberries (Creech 1987b). In that study, 6-foot deep holes were backfilled with composted pine bark mixed with the native soil (a Darco sand) prior to planting, and then growth was measured for several years. There was no impact on growth and random observations of root system profiles suggested that root systems remained in the 1-foot horizon, with most roots at the surface near the mulch/soil interface. Returning to water quality factors, another study monitored the effects of four water qualities, four medias and three gypsum rates on container growth of `Tifblue’ rabbiteye blueberries (Creech et. al 1989a). Gypsum didn’t ameliorate the negative impact of increasing Na, and levels above 50 PPM irrigation water Na were associated with higher leaf tissue Na concentrations and less growth. In a 1987-1991 study, we examined the influence of three above-ground mulch treatments (weed barrier, continuous bark, and none) and four in-ground amendment treatments (peat moss, pine bark, pine bark continuous, and none) on growth of ‘Climax’ and ‘Brightwell’ rabbiteye blueberries (Creech 1990a). Surprisingly, the 4-foot wide DewittR weed barrier treatments resulted in superior plants, regardless of below-ground treatments, perhaps by providing a wider irrigation pattern.

In 1986-88, soil samples, irrigation water samples, and leaf tissue was collected from a wide range of blueberry farms in East Texas (Creech et. al 1989b, Creech 1990a). A ranking system was used to rate plant vigor and health was used to create parameters associated with the best plants. That project evolved into two studies with multiple collaborators across the South, an investigation of the foliar elemental analysis of Southern Highbush, Rabbiteye, and Highbush blueberries in the southern United States, with analysis at the SFA Soil and Plant Tissue Testing Laboratory (Creech 1990b, Clark et al. 1994, Gupton et. al 1996)). At Mill Creek Blueberry Farm there was concern that a long-term strategy to provide nutrients only through a drip irrigation system might be less than prudent, that blueberry plants were perhaps compromised by a limited nutrient and moisture zone. We initiated a field survey of the impact of eight years of fertigation on soil pH, conductivity and nutrient levels, and found that while the “water and nutrient zone was only a meter wide,” plant growth remained vigorous (Creech and Bickerstaff 1996).

MILL CREEK BLUEBERRY FARM, A CASE STUDY

Mill Creek Blueberry Farm was located six miles west of Nacogdoches on Highway 59 and fifty acres of ‘Climax’, ‘Premier’, ‘Brightwell’, ‘Tifblue’ and ‘Powderblue’ were planted in 1988. Prior to this planting, a one-acre test plot was provided to the SFA blueberry research effort, which is currently used to evaluate new blueberry germplasm. The site is very well drained, low pH (5.2), Darco sand, and the water source is an eight-acre spring fed lake of very high quality water.

The preplant strategy for this 50-acre commercial farm involved clearing the primarily scrub forest and smoothing the acreage. That was followed by a crop of pearl millet which was mowed and tilled under. Prior to planting one-gallon containers, approximately 90 yd3 of composted pine bark was banded down the rows (15-feet spacing between rows) and tilled in. After planting, the rows were mulched on the surface with another 90 cubic yards of pine bark. The drip irrigation system has performed well for 20 years without replacement of field lines. Plants receive about 8 gallons of water per plant per day and the fertigation program system delivers 3 to 5 lbs. N/acre/week, normally delivered in two to four pulses each day. Late spring freezes in the early 1990s dramatically reduced production. A sprinkler system for frost protection was installed in 1993 and has benefited the field many times when conditions allowed. A large field study in 1993 and 1994 tested five cryoprotectants which failed to improve bloom survival during freeze events in those years (Thomas and Creech 1996). In 2006, a 15-acre field of ‘Tifblue’ and ‘Powderblue’ was planted adjacent to the blueberry field. Field performance has been good with a high production mark 2007 with 751,072 lbs picked, packed and sold (11,210 lbs./acre). Average production for the last five years in lbs/acre is as follows: ‘Climax’ (3708), ‘Premier’ (5345), ‘Tifblue’ (6573), ‘Brightwell’ (7974), and ‘Powderblue’ (13794). Mill Creek Blueberry Farm used to serve as the cooperator site for Stephen F. Austin State University’s blueberry germplasm evaluation program, a cooperative project with the USDA, as well as a platform for a number of blueberry research projects. That field is no longer in operation (the business closed in 2013) for reasons best not discussed here.

PLANTING – Blueberries are generally spaced 4 to 6’ apart in rows 12 to 15’ apart. We generally recommend the wider spacing for Rabbiteyes, the closer spacing for Southern Highbush varieties. If possible, it’s always best to remove all woody weeds from the site prior to planting. A crop of pearl millet or forage sudan be grown the year before planting – a high tonnage crop that shades the ground and kills many weeds and provides high organic matter content for the initial year of establishment. In general, most growers plant one gallon plants, but bareroot plants are suitable if they are of suitable size. Care must be taken never to set plants too deep, a common grower mistake. Blueberries should be set at the level they grew in the container or nursery field. If possible, plants should be established in December or January. In Southeast Texas, SHB growers generally plant on very distinct raised beds that shed water easily. Beds are generally mulched with a wide variety of materials including pine bark, wood chips, rice hulls. At this writing, pine bark generally $10 – $15 per cubic yard.

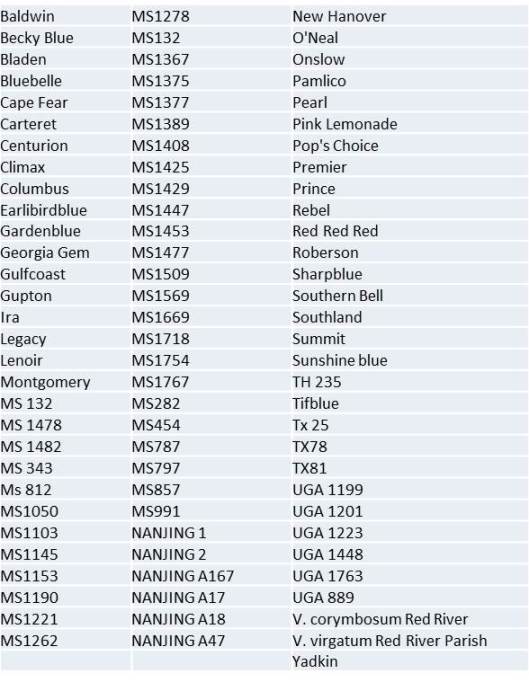

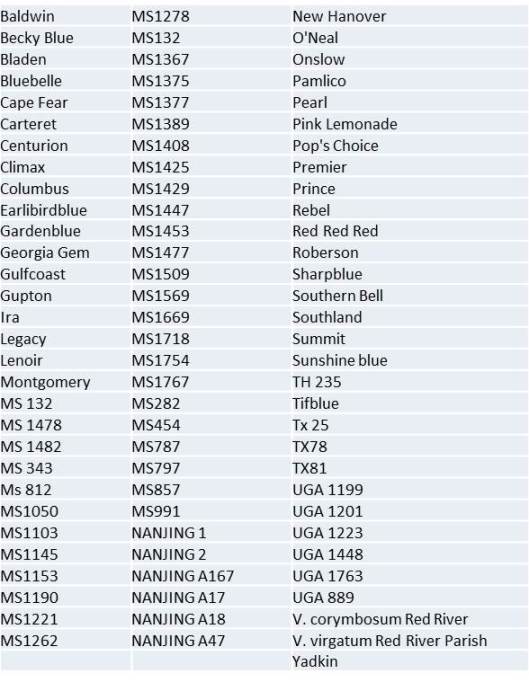

VARIETIES – There are two types of blueberries adapted to East Texas: Rabbiteye blueberries (RE) and Southern Highbush (SHB). Rabbiteyes comprise the bulk of southern production.

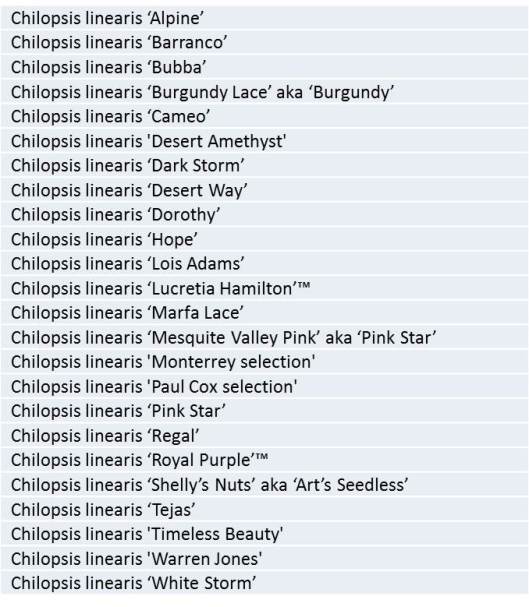

Blueberry varieties and selections Feb 2020

Blueberry variety plots, N end PNPC, SFA Gardens

SOIL – In general, a sandy to sandy loam soil is preferred. More important, perhaps, is the surface and internal drainage characteristics of the soil. Blueberries like well drained soils. Heavier soils can be used but rows should be elevated into mild “berms” to improve drainage. The 1986-88 field survey allowed SFA to provide benchmark soil preference information to potential blueberry growers. The following results are values that were most often associated with good fields and healthy plants. The following data indicates the soil nutrient characteristics of superior fields and plants. If a soil has characteristics outside of these parameters, further study is warranted!

|

|

|

|

|

Soil |

|

|

|

|

|

|

PPM |

|

| YEAR |

pH |

Cond |

P |

K |

Ca |

Mg |

| 1986 |

4.6 |

85 |

29 |

53 ± 22 |

232 ± 102 |

42 ± 15 |

| 1987 |

5.1± .3 |

55±25 |

22±11 |

13±49 |

280±84 |

46±21 |

| 1988 |

5.2± .6 |

153±29 |

29±19 |

102±46 |

539±211 |

68±25 |

| x |

4.9±.5 |

92±70 |

27±16 |

52±37 |

325±123 |

50±20 |

|

|

|

Soil |

|

|

|

|

|

PPM |

|

|

| YEAR |

Na |

Cu |

Fe |

Mn |

Zn |

| 1986 |

36±12 |

0.6±.4 |

86±80 |

29±30 |

1.0±1.4 |

| 1987 |

57±29 |

.5±.4 |

73±63 |

38±75 |

2.4±1.2 |

| 1988 |

37±11 |

.7±.8 |

129±121 |

30±41 |

3.0±2.1 |

| x |

43±18 |

.6±.5 |

92±84 |

32±48 |

2±1.5 |

There was a strong correlation between healthy plants and soil pH, conductivity, Ca, and Na. Blueberry plants were healthier when the pH was about 5 and conductivity, Ca, Mg, Na and bicarbonate levels quite low.

IRRIGATION – In general, growers use drip irrigation to provide water during the growing season in East Texas. Growers generally design their fields to provide 8 to 12 gallons of water per plant per day. Sites with heavier soils may be able to get by with 6 gallons per plant per day. Note. Care must be taken to place emitters at the plant – this is critical during the first year or two of establishment when root systems are small. Growers on sandy soils or those using fast draining media in the root zone should consider a strategy of irrigating two or three times per day to “pulse” the desired amount into the root zone. There’s no point in irrigating deep when roots are right near the surface. It’s all about water quality. Surface sources are generally fine but still need testing. Blueberries like low salt water. They are particularly sensitive to irrigation water that has a substantial of Ca, Mg, Na and bicarbonates. What is interesting about the following means is the rather low level of Na in the irrigation water. The converse was true. Those fields using irrigation water with values much above the numbers below, well, they were unthrifty, off color, and not growing well.

|

|

|

|

|

IRRIGATION WATER |

|

|

|

|

|

|

PPM |

|

| YEAR |

pH |

cond.(umhos/cm) |

Ca |

Mg |

Na |

Bicarb (meg/l) |

| 1986 |

6.7±.9 |

178±190 |

15.2±26.9 |

4.3±6.8 |

10.5±12.5 |

.7±1 |

| 1987 |

7.3±1.1 |

182±209 |

15.9±31.7 |

5.1±6.2 |

13.2±16.3 |

.9±1.1 |

| 1988 |

7.2±.5 |

213±207 |

10.9±17.8 |

4.6±6.8 |

30.1±4.4 |

1.2±1.1 |

| x |

7.0±.9 |

188±201 |

14.4±26.3 |

4.7±6.6 |

16.3±19.3 |

.9±1.1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FROST – Spring frost is the number one problem facing growers. Blueberries tend to bloom at or near the time of the last few spring frosts. Temperatures below 28oF freezing can be devastating to open blooms. A high elevated north-facing slope is generally preferred (warm air rises, cold air sinks). A rolled and packed smooth surface is considered better than a grassed alley. Sprinkling for frost protection can protect blooms from freeze damage but conditions must be right (no to very little wind – good coverage – and low temperatures not lower than the capacity of the sprinkler system). A 60 gpm/acre rate will generally protect blueberries into the mid – twenties. 150 gpm/acre will protect into the teens. A few growers in the southeastern part of Texas use fans to protect plants from spring frost with the general reported acreage around 12 acres per fan. At $30,000 per fan, the investment is considered substantial.

PESTS – When blueberries were first introduced, there were few problems with pests. As acreage increased, that no longer was true. Midges at bloom are a problem and spray applications may be necessary in the early season. then. At other times, sporadic pest problems may emerge. Mummy berry requires a spray program as well. Some fields more affected than others and some years are worse than others. Preventative sprays are important. Southeast Texas growers report cleaner, healthier foliage under a various arsenal of fungicide, leaf feed commercially available products.

WEED CONTROL

Weeds are a major problem especially in the first few years of establishment. Growers commonly use hand weeding, mulching, and careful application of herbicides. Glyphosate can be a remarkable tool to the first planting – but many growers learn the hard way about drift and what happens when the applicator is sloppy. Glyphosate-hit plants take years to nurse back to health. Weed barrier is another option, generally a 6’ wide strip that is applied so the edges are tucked into a furrow and recovered with soil. A Slit or oval is “burned” at the correct spacing prior to planting.

FERTILIZING – Blueberries do not need a high fertility rate. Many growers have switched to feeding plants via a drip irrigation system: fertigation. A rate of 3 to 5 lbs of N per acre per week during the growing season is a common recommendation and feeding at every watering is a prudent strategy. This provides a light steady rate of nutrients in the soil solution during the active growing season. Soluble sources include blueberry specials, ammonium sulfate (can be used to drive soil pH down), and urea generally keeps pH somewhat stable or at background levels. “Blueberry Special” fertilizers, while they cost more, are acid forming and also provide additional micronutrients. Growers should monitor pH and conductivities to keep levels within acceptable parameters. If granular fertilizers are used, it is important to keep fertilizer away from the crown. An ounce of fertilizer around the periphery of the drip line and distributed as uniformly as possible is a good practice. Growers in the southeast are reporting good results with various commercially available nutrient systems. Leaf tissue analysis provides some indication of the health of plants. Unfortunately, leaf nutrient deficiency/toxicity symptoms are often confounding. Unthrifty plants can show all kinds of symptoms, many mimicking classic elemental deficiency/toxicity symptoms. That said, the following leaf tissue analysis describes the nutrient levels of healthy blueberry plants.

|

|

|

|

|

LEAF TISSUE |

|

|

|

|

|

Percent |

|

|

|

|

| Year |

N |

P |

K |

Ca |

Mg |

S |

|

| 1986 |

1.35±.16 |

.08±.01 |

.44±.11 |

.31±.05 |

.14±.03 |

.15±.02 |

|

| 1987 |

1.14±.09 |

.08±.03 |

.52±.06 |

.27±.09 |

.13±.05 |

.14±.02 |

|

| 1988 |

1.28±.13 |

.07±.01 |

.27±.07 |

.25±.05 |

.14±.05 |

.12±.03 |

|

| x |

1.26±.13 |

.08±.02 |

.43±.08 |

.28±.06 |

.14±.04 |

.14±.02 |

|

|

|

|

PPM |

|

|

| Year |

Fe |

Mn |

Na |

Zn |

Cu |

| 1986 |

87±111 |

81±38 |

84±52 |

84±52 |

NA |

| 1987 |

133±243 |

75±101 |

75±101 |

161±286 |

.5±.3 |

| 1988 |

256±364 |

46±12 |

46±12 |

265±406 |

.5±.3 |

| x |

145±220 |

70±53 |

70±53 |

156±221 |

.5±.3 |

The most progressive growers usually have an aggressive approach to experimenting with nutrient sources, mulch sources, and watering regimes. The three tables above for soil, irrigation water, and leaf tissue analysis can be quite useful. If most of the parameters are on the mark, but both soil and leaf K are showing a bit low, it may be time for a K application.

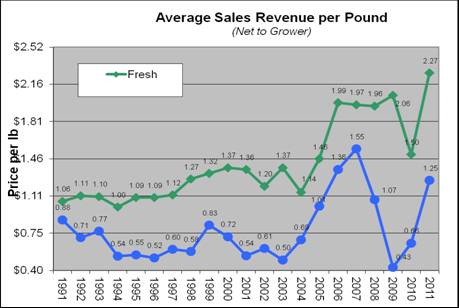

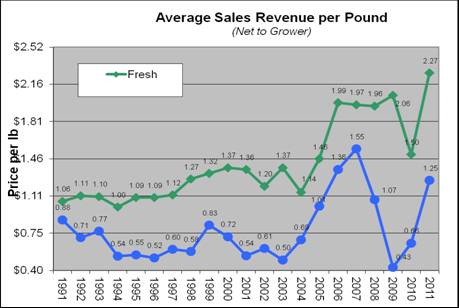

ECONOMICS – Every field will have a different investment cost and a business plan should help point the way to profitability. The graph below describes the pricing pattern for blueberries 1991-2011 for one TBMA producer. Green line is fresh; blue line is frozen prices. More recent pricing is available through market news reports.

CONCLUSIONS

Rabbiteye and SHB blueberries offer growers a crop that appears to have long term consumer appeal. In 2024, the impact of Mexico and Peruvian blueberries has changed the pricing structure and profitability of blueberries in Texas. The science and art of growing healthy blueberry plants in our region is part of an evolving industry.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author expresses gratitude to the graduate and undergraduate students who provided the hard work needed to start, manage, and complete blueberry research projects. The author expresses thanks to the many blueberry farmers in East Texas and Louisiana who never failed to be hospitable, gracious and supportive of our program. Finally, the author expresses special thanks to the past General Manager of Mill Creek Farms, Mr. Henry Sunda, who has embraced our work, gave great counsel, capitalized on our results when they made sense, and ended up being a fast friend.

Literature Cited

Bennett, G.W., Creech, D., and Young, J. 1984. Influence of media, N rate, and incorporated slow release micronutrients on growth and leaf nutrient content of containerized blueberries, Vaccinium ashei Reade. HortSci. 19(3): 563 (abst.).

Creech, D.L. and Dale, L. 1982. Growth of container-grown, large barefoot, and small barefoot rabbiteye blueberry nursery plants in the field. Proceedings of the Texas Blueberry Growers Association: 26-30.

Creech, D. and White, J. 1982. Influence of slow-release fertilizers and organic matter on establishment of rabbiteye blueberries. Proceedings of the Texas Blueberry Growers Association: 21-26.

Creech, D., and Dale, L. 1983. Growth, yield, and leaf elemental content of container-grown, large bareroot, and small bareroot ‘Tifblue’ rabbiteye blueberry nursery plants in the field. HortSci. 18(4): 561 (abst.).

Creech, D.L. and Young, L. 1983a. Influence of nitrogen source and rate on growth and leaf elemental content of ‘Delite’ rabbiteye blueberries. HortSci. 18(4): 583 (abst.).

Creech, D.L. and Young, L. 1983b. Influence of sulfur and rate on soil pH and rabbiteye blueberry growth in the presence of high pH irrigation water. Proceedings of the Texas Blueberry Growers Association: 17-23.

Creech, D., Richardson, J., and Young, L. 1985. Influence of mist pH, slow-release micronutrients and media on rooting of peach and rabbiteye blueberry softwood cuttings. HortSci. 20(3): 538 (abst.)

Creech, D. 1986a. The influence of fertilizer placement on growth and nutrient distribution on a split-root study of azalea and rabbiteye blueberry. Proceedings of the Texas Blueberry Growers Association: 28-34.

Creech, D. 1986b. Experiment shows rabbiteye blueberry is poor lateral translocator of nutrients. Texas Hort. 13(5): 12.

Creech, D. 1986c. Banding fertilizer not recommended for blueberries. Texas Hort. 12(9): 9

Creech, D. 1986d. Study shows need for quality irrigation water. Texas Hort. 13(4): 11.

Creech, D., Patten, K. and Neuendorff, E. 1986. Influence of sodium on growth and leaf elemental content of ‘Tifblue’ rabbiteye blueberries. HortSci. 22(5): 717 (abst.).

Creech, D. 1987a. The influence of three mulch and six incorporated media treatments on root and shoot growth of ‘Climax’ and ‘Brightwell’ rabbiteye blueberries. HortSci. 22(5): 1095 (abst.).

Creech, D. 1987b. The influence of shallow and deep placement of organic matter in the planting hole on root and shoot growth of rabbiteye blueberries. HortSci. 22(5): 1104 (abst.).

Creech, D. 1987c. Blueberry studies reveal “there’s no such thing as a fertilization recipe”. Fruit South 8(4): 6-8.

Creech, D. 1987d. Banding not a good idea; apply fertilizer evenly around plant. Texas Hort.13(5): 12.

Creech, D., Bales, M., Young, L., and Bell, T. Influence of four water qualities, four medias and three gypsum rates on growth of `Tifblue’ rabbiteye blueberries. HortSci. 24(5): 749 (abst).

Creech, D., Bell, T., Dale, L., and Young, J. 1989b. Results of the 1986-88 blueberry field study. Proceedings of the Texas Blueberry Growers Association: 83-94.

Creech, D. 1990a. Final Report on the polyfabric, bark, and zero above-ground mulch study. Proceedings of the Texas Blueberry Growers Association: 40-48.

Creech, D. 1990b. Nutritional parameters of southern highbush, highbush, and rabbiteye blueberries. Proceedings of the Texas Blueberry Growers: 56-61.

Creech, D., and Bickerstaff, G. 1996. Effects of a long-term fertigation program on soil pH, conductivity and nutrient levels. HortScience 31 (5): 751 (abst.)

Clark, J., Creech, D., Austin, M., Ferree, M., Lyrene, P., Mainland, M., Makus, D., Neuendorff, E., Patten, K., and Spiers, J. 1994. Foliar elemental analysis of Southern Highbush, Rabbiteye, and Highbush blueberries in the southern United States. HortTechnology 4(4): 351-355.

Gupton, C., Clark, J., Creech, D., Powell, A., and Rooks, S. 1992. Genotype X Location Interactions in Blueberry. HortSci. 27(6): 657.

Thomas, G., and Creech, D. 1994. Cryoprotectants and Frost Protection . . . Are they worth the money? Proceedings of the Texas Blueberry Growers Association: 9-17.

White, J., and Creech, D. 1981. The influence of slow release fertilizers on establishment of Rabbiteye blueberries. Proceedings of the Texas Blueberry Growers Association: 10-12.

Young, L., and Creech, D. 1983. Influence of slow-release micronutrients and organic matter on growth of ‘Tifblue’ rabbiteye blueberries. HortSci. 18(4): 584 (abst.).

At SFA Gardens, we have an interesting P. serrulata clone that came to our garden many years ago via Sherwood Akin, Sibley, Louisiana. It was one of his seedlings, selected because it had a superior shape and form than other seedlings. In the Mast Arboretum our best specimen gets good sun and moisture – it’s actually adjacent to wet spot in the garden. This football-shaped 12’ shrub has endured hurricanes, floods, and the drought and heat of 2010 and 2011. It’s never been pruned – except for a few cuttings every now and then. White flowers are arranged as bright, 6-8” diameter clusters. New growth is slightly pinkish bronze. The springtime flower clusters are followed by fruit clusters of red berry-like fruit which persist a bit into the winter.

At SFA Gardens, we have an interesting P. serrulata clone that came to our garden many years ago via Sherwood Akin, Sibley, Louisiana. It was one of his seedlings, selected because it had a superior shape and form than other seedlings. In the Mast Arboretum our best specimen gets good sun and moisture – it’s actually adjacent to wet spot in the garden. This football-shaped 12’ shrub has endured hurricanes, floods, and the drought and heat of 2010 and 2011. It’s never been pruned – except for a few cuttings every now and then. White flowers are arranged as bright, 6-8” diameter clusters. New growth is slightly pinkish bronze. The springtime flower clusters are followed by fruit clusters of red berry-like fruit which persist a bit into the winter.

Sam Joel-Schafer with an Agave americana ssp. protoamericana. Sam was the youngest in our expedition, a biochemistry graduate and Spanish-proficient rebel without a cause, cheerfully struggling for a career in juggling, a hand stands in the middle of a highway guy, and at last account doing quite well as a professional gypsy in South America. Sam was probably the most complete and self-satisfied member of our troop.

Sam Joel-Schafer with an Agave americana ssp. protoamericana. Sam was the youngest in our expedition, a biochemistry graduate and Spanish-proficient rebel without a cause, cheerfully struggling for a career in juggling, a hand stands in the middle of a highway guy, and at last account doing quite well as a professional gypsy in South America. Sam was probably the most complete and self-satisfied member of our troop.

Greg Starr, owner of Starr Nursery, Tuscon, Arizona, wondering how he got here and how to get down. Greg is a fine botanist, teacher, and nurseryman of immense reputation and insight. Greg wrote the description of Agave ovatifolia, the rare whale’s tongue Agave found by Lynn Lowrey growing between 3000′ and 7000′ elevation in Nuevo Leon, Mexico (Starr, 2004). Greg’s nursery is a small but intense backyard mail order nursery. With a desert lily focus, this is dangerous work and best attacked by using rolled up newspapers, welder’s gloves, and a whole lot of pain management.

Greg Starr, owner of Starr Nursery, Tuscon, Arizona, wondering how he got here and how to get down. Greg is a fine botanist, teacher, and nurseryman of immense reputation and insight. Greg wrote the description of Agave ovatifolia, the rare whale’s tongue Agave found by Lynn Lowrey growing between 3000′ and 7000′ elevation in Nuevo Leon, Mexico (Starr, 2004). Greg’s nursery is a small but intense backyard mail order nursery. With a desert lily focus, this is dangerous work and best attacked by using rolled up newspapers, welder’s gloves, and a whole lot of pain management. Janet Creech, my adventure-friendly, cookie-making wife, wanted to go on the trip right from the start. While I was a bit skeptical, I finally relinquished provided she promises to always be cheerful, never complain no matter what. For the most part, that is exactly what happened. As the only lady in an otherwise unkempt and untidy group, she found the whole experience a great adventure but probably not worth repeating.

Janet Creech, my adventure-friendly, cookie-making wife, wanted to go on the trip right from the start. While I was a bit skeptical, I finally relinquished provided she promises to always be cheerful, never complain no matter what. For the most part, that is exactly what happened. As the only lady in an otherwise unkempt and untidy group, she found the whole experience a great adventure but probably not worth repeating. On a canyon road near Las Varas, Mexico

On a canyon road near Las Varas, Mexico

Images of Agave potrerana in bloom near Las Varas, Mexico, June 12, 2006

Images of Agave potrerana in bloom near Las Varas, Mexico, June 12, 2006

Common Name: Chinese Emmenopterys

Common Name: Chinese Emmenopterys