Here’s a little trip down memory lane. This goes back to a June 2006 trip to northern Mexico hunting plants, studying plants, and talking plants. Our little tribe can only be characterized as an eclectic band of like minded souls, hell bent to document a wide range of desert lilies (Agaves, Hesperaloes, Yuccas, Dasylirions, and Nolinas). We were a band of horticulturists who never met a plant we didn’t like. Our mission was simple: Take three vehicles, camping equipment, act like we knew what we were doing, do our best to stay out of trouble, and when needed, we could count on my Spanish to sidestep our way out of jail. That was our plan and for the most part, it worked.

Here’s the group of enthusiastic plantsmen that made the trip

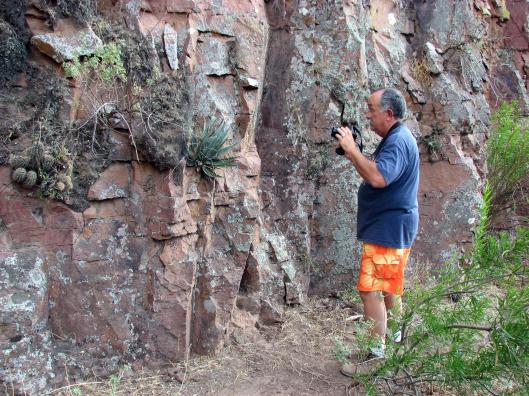

Near Las Varas, Mexico, George Hull at the base of the slope that leads to Agave Potrerana

George was at Mountain State Nursery, Phoenix, Arizona in 2006 and he’s now retired in Portland, Oregon, enjoying the good life. George remains the ultimate plantsman, designer, teacher, plant-savvy fellow and I deemed him the senior citizen of our group, even though he’s the same age as me but he acts more senior than I do). George is blessed with a sense of humor best taken in small doses.

Brian Kemble with a close friend, Agave scabra. Since 1980, Brian has been the Horticulturist at the Ruth Bancroft Gardens, Walnut Creek, California. With a required BA in Philosophy, he has many years of experience in the wonderful world of desert succulents. Of the group, Brian was the quickest to reach the mountain top, first to find a sought-after plant, and incessantly passionate about the world of desert and dry mountain plants.

Rob Nixon, environmental assessment professional from California, and a snake, spider and desert plant enthusiast. Rob was eager to bring spiders and snakes he had caught into the camp for what he thought was a good show and tell opportunity. Most of the team thought it was a poor idea. Janet would walk away.

Sam Joel-Schafer with an Agave americana ssp. protoamericana. Sam was the youngest in our expedition, a biochemistry graduate and Spanish-proficient rebel without a cause, cheerfully struggling for a career in juggling, a hand stands in the middle of a highway guy, and at last account doing quite well as a professional gypsy in South America. Sam was probably the most complete and self-satisfied member of our troop.

Sam Joel-Schafer with an Agave americana ssp. protoamericana. Sam was the youngest in our expedition, a biochemistry graduate and Spanish-proficient rebel without a cause, cheerfully struggling for a career in juggling, a hand stands in the middle of a highway guy, and at last account doing quite well as a professional gypsy in South America. Sam was probably the most complete and self-satisfied member of our troop.

Sean Hogan, owner of Cistus Nursery, Portland, Oregon, admiring a wonderfully old mound of Mammillaria. Sean is an author, lecturer, landscaper, a walking encyclopedia on anything that has something to do with an obscure plant, and an introducer of new plants and new ideas in the Pacific Northwest. While his mastery of puns was punishing, Sean did bring a needed touch of sensitivity, culture and civility to our group

Greg Starr, owner of Starr Nursery, Tuscon, Arizona, wondering how he got here and how to get down. Greg is a fine botanist, teacher, and nurseryman of immense reputation and insight. Greg wrote the description of Agave ovatifolia, the rare whale’s tongue Agave found by Lynn Lowrey growing between 3000′ and 7000′ elevation in Nuevo Leon, Mexico (Starr, 2004). Greg’s nursery is a small but intense backyard mail order nursery. With a desert lily focus, this is dangerous work and best attacked by using rolled up newspapers, welder’s gloves, and a whole lot of pain management.

Greg Starr, owner of Starr Nursery, Tuscon, Arizona, wondering how he got here and how to get down. Greg is a fine botanist, teacher, and nurseryman of immense reputation and insight. Greg wrote the description of Agave ovatifolia, the rare whale’s tongue Agave found by Lynn Lowrey growing between 3000′ and 7000′ elevation in Nuevo Leon, Mexico (Starr, 2004). Greg’s nursery is a small but intense backyard mail order nursery. With a desert lily focus, this is dangerous work and best attacked by using rolled up newspapers, welder’s gloves, and a whole lot of pain management.

Janet Creech, my adventure-friendly, cookie-making wife, wanted to go on the trip right from the start. While I was a bit skeptical, I finally relinquished provided she promises to always be cheerful, never complain no matter what. For the most part, that is exactly what happened. As the only lady in an otherwise unkempt and untidy group, she found the whole experience a great adventure but probably not worth repeating.

Janet Creech, my adventure-friendly, cookie-making wife, wanted to go on the trip right from the start. While I was a bit skeptical, I finally relinquished provided she promises to always be cheerful, never complain no matter what. For the most part, that is exactly what happened. As the only lady in an otherwise unkempt and untidy group, she found the whole experience a great adventure but probably not worth repeating.

On a canyon road near Las Varas, Mexico

On a canyon road near Las Varas, Mexico

The focus of this trip was mainly Agaves and other desert lilies, with several members on an intense succulent hunt, with particular emphasis on Escheverias, Crassulas, and other euphorbs of importance. It’s no secret I like real plants – big trees, shrubs, woody vines – but I did find it inspiring to travel with folks obsessed by plants less than the size of a salad plate. Every now and then I would demand a tree fix. Connected by walkie talkies, our caravan would pull to a stop to let me scramble down to the river to marvel at thousand year old Montezuma cypresses – while the rest would hang out at the road waiting on my return grumbling about losing time. Some of the escheverias we sought involved hiking miles over rough terrain to find some rare Escheveria only appreciated by getting down on your hands and knees to take it all in.

First, let’s say any plantsman who visits the wild lands of Mexico can’t help but fall in love with the botany. Once wetter and drier, once connected to the botany of the SE USA, drier and hotter times have forced plants into an evolutionary torture test. If you like desert plants, there’s no place like Mexico. If you like Agaves, this is heaven.

We started our expedition at the border town of Douglas, Arizona, and headed south along the San Madre Oriental mountain range – scooting between desert and mountain flora as we made our way south to just north of Mexico city. The return trip took us north and west through some of the San Madre Occidental mountain range before crossing back into the USA at Nogales, Arizona. It’s remarkable how remote and beautiful so much of Mexico’s mountain land remains. While there’s a genuine conservation ethic brewing, it’s also sadly true that livestock and humans have placed amazing pressure on all but the most remote regions of the country.

While we found, photographed and documented over 20 Agave species during the 2006 trip, there was one species that made the trip worthwhile, Agave potrerana. We caught it in bloom on the first day of our trip – 29o 21.672N, 106o 28.825W, and 5218’ elevation – on the road to Las Varas. Along the bumpy road into a canyon, we found Agave parryi scattered here and there in the mountains. About four miles into the canyon, one of our tribe spotted the snake-like red yellow inflorescence peeking over a ledge. After a brisk climb and crawl up a slope too steep for any normal human being, the group basked in the glory of this strange plant in flower. Smiles and handshakes were in order, about 100 digital and film images were taken, and seed was found from plants nearby. It was a good start to the trip.

Images of Agave potrerana in bloom near Las Varas, Mexico, June 12, 2006

Images of Agave potrerana in bloom near Las Varas, Mexico, June 12, 2006

Agave potrerana is rarely encountered but can be found at elevations between 5,000 and 8,000 feet in northern Coahuila and Chihuahua, essentially finding a home in sunny spots in oak-pine-grassland habitats. This part of north-central Mexico gets temperatures well below freezing in winter and this Agave is quite cold-hardy in cultivation, enduring temperatures at least down to the low 20’s Fahrenheit without injury. While Tony Avent reports it has withstood temps in the lower teens, we haven’t found that to be the case. As far as we can determine, it’s only marginally hardy here in the Pineywoods of East Texas and I’ve lost it several times during the past thirty years.

A. potrerana is not often seen in cultivation in USA gardens and it’s rather hard to find in nurseries although it is occasionally listed in Plant Delights and other specialty nursery catalogs. The plants are typically found as a single, with green or blue-green leaves about 3 feet long. The densely-flowered inflorescence with red to orange to red flowers can only be described as a showstopper. The infloresence is unbranched and ranges from 12 feet to over 20 feet tall.

I’ve only been back to the wild lands of Mexico once since this 2006 trip and things have changed. Political turmoil, gangs, and a penchant to kidnap foreigners and hold them for ransom has put a bit of a damper on trips to the back country. Add to the fact that my SFA Gardens staff didn’t think if I was held for ransom they could raise much over $3000 to get me back. Yet, this is a special place with a magical and wonderful botany, the kindest people in the world, and there’s a vista around every turn of the road. If you don’t like agaves, you might find the spirits of them refreshing. One of our stops was to get some gasoline and some pulque. It escapes me why the two were being sold at the same tienda but after a nip or two of pulque, it all seemed to make sense.

SUGGESTED REFERENCES:

Gentry, H.S. 1982. Agaves of Continental North America. The University of Arizona Press, Tuscon, Arizona. 670 pp.

Irish, M. and G. Irish. 2000. Agaves, Yuccas and Related Plants. Timber Press, Portland, Oregon. 312 pp.

Mason, C.T. and P.B. Mason. 1987. A Handbook of Mexican Roadside Flora. The University of Arizona Press, Tuscon, Arizona. 380 pp.

Standley, P.C. 1920. Trees and Shrubs of Mexico. Reprinted in 1982 by J.Cramer of Strauss and Cramer GmbH, D-6945 Hirschberg 2 (ISBN 3-7682-1288-2). 1721 pp.

Starr, G. 2004. Agave ovatifolia: the whale’s tongue agave. Cactus and Succulent Journal, 2004 (Vol. 76) (No. 6) 303-307.

Common Name: Chinese Emmenopterys

Common Name: Chinese Emmenopterys

Mahonia gracilis on a mountain side east of Saltillo.

Mahonia gracilis on a mountain side east of Saltillo. Mahonia gracilis in full sun at the Mast Arboretum.

Mahonia gracilis in full sun at the Mast Arboretum. Mahonia trifoliata at SFA Gardens

Mahonia trifoliata at SFA Gardens M. trifoliata X M. swaysei, a naturally occurring hybrid in Central Texas.

M. trifoliata X M. swaysei, a naturally occurring hybrid in Central Texas.

Shiny green leaves are 7.5-10 (2.9-3.9 in.) long and 2-3 cm. (.8-1.2 in.) wide and are lanceolate to narrowly elliptical with a pointed apex. Acorns are small, 1.5 cm. (.6 in.) long, somewhat narrow and without a significant peduncle. The cup is shallow and covers only 1/4 to 1/3 of the cup. The nomenclature of Q. canbyi is complicated and there are a number of synonyms. It has been described as a variety of Q. graciliformis in the south of its range, northern Mexico, but most authors consider Q. gracilformis as a form of Canbyi oak. It is also associated with Q. langtry, which is also thought to be a form of Q. canbyi found near Langtry, Texas. Most impressive is the extremely clean foliage.

Shiny green leaves are 7.5-10 (2.9-3.9 in.) long and 2-3 cm. (.8-1.2 in.) wide and are lanceolate to narrowly elliptical with a pointed apex. Acorns are small, 1.5 cm. (.6 in.) long, somewhat narrow and without a significant peduncle. The cup is shallow and covers only 1/4 to 1/3 of the cup. The nomenclature of Q. canbyi is complicated and there are a number of synonyms. It has been described as a variety of Q. graciliformis in the south of its range, northern Mexico, but most authors consider Q. gracilformis as a form of Canbyi oak. It is also associated with Q. langtry, which is also thought to be a form of Q. canbyi found near Langtry, Texas. Most impressive is the extremely clean foliage.